In honor of Women’s History month, a photography exhibition was held from March 4-8 within the Warrior Cross Cultural Center on the second floor of the Vasche Library, room L203. The exhibition, titled Dichos, showcases the photography and video artwork of CSU Stanislaus alumna Monica Crystal Ocegueda.

Ocegueda explains that the title, Dichos, represents common Mexican sayings that have been passed down through the culture for generations.

“These sayings often hold truths and lessons,” Ocegueda says, “especially for women and young children. Some dichos can be harmful towards women, especially the ones included in this exhibition.”

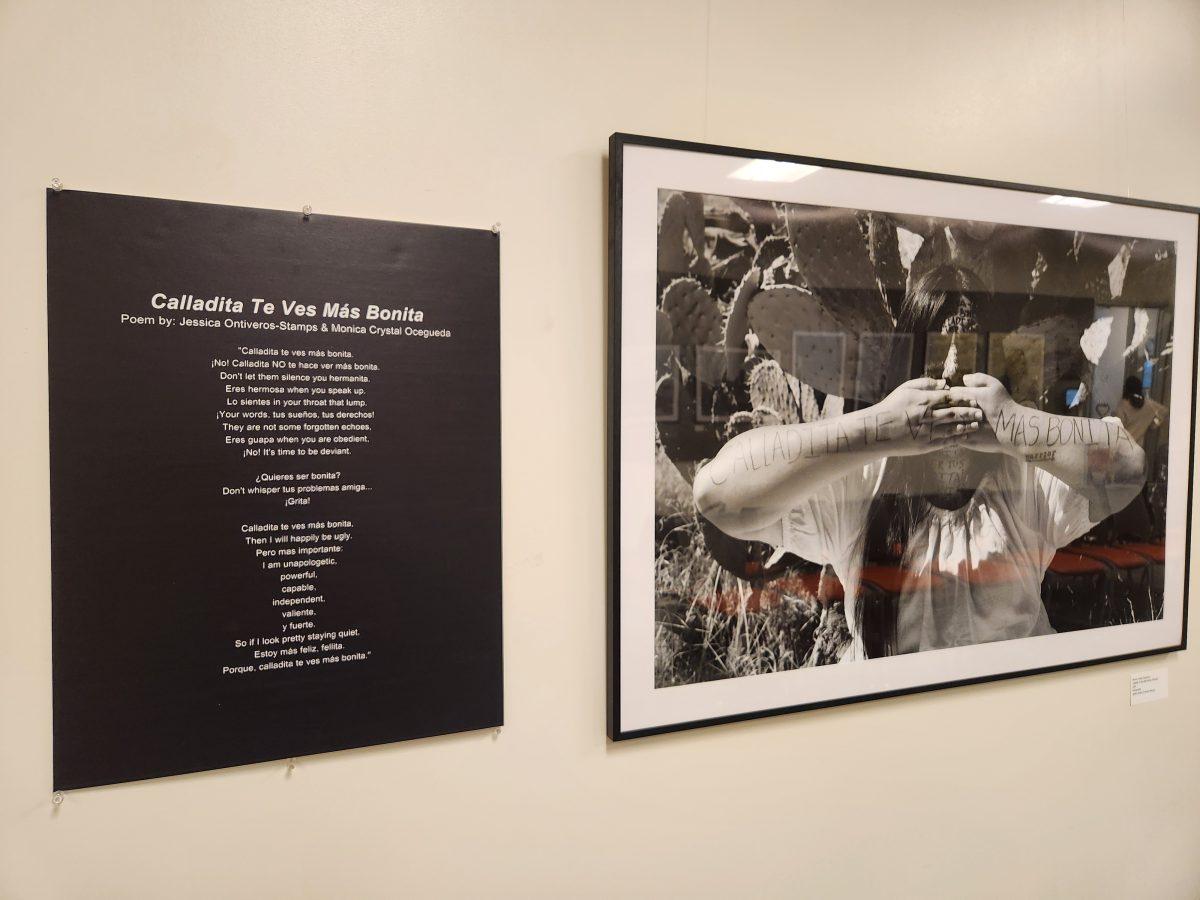

The first item of note when entering the exhibition room is the flat-screen TV mounted on the wall, playing a YouTube video titled, Calladita Te Ves Más Bonita, one such dichos.

Speakers on the ceiling recite the poem of the same name, written by Jessica Ontiveros-Stamps and Monica Ocegueda and narrated by Monica Ocegueda. Written in both Spanish and English, the words of the poem reject the idea that women are more beautiful when silent and implore women to speak up and uplift their voices.

Surrounding the TV hangs another installation, El Que Nace Para Tamal Del Cielo Le Caen Las Hojas, which consists of tamale husks hung from clear strings and bearing the word poderosa—powerful. The title of the installation is a dichos meaning that the life that is destined for you will come to pass.

Black-and-white photographs line the longest two walls of the exhibition. The photographs along the wall closest to the entrance work hand-in-hand with the nearby El Que Nace Para Tamal Del Cielo Le Caen Las Hojas installation.

In these photographs, model Sarahi Jiménez stands in a field as tamale husks rain gently down around her. In one, she clutches a bouquet of husks to her chest; in another, she reaches upwards, trying to catch a husk as it falls.

The next photograph in the series shows Jiménez holding one of the husks above her head as she gazes at the word “poderosa” written across the inner shell. The shot is taken from a low angle that imbues Jiménez with a sense of strength and power.

Fellow alumna Berta Cerbantes participated in Ocegueda’s work as a model and has a personal connection to dichos. As a little girl, Cerbantes grew up hearing these sayings and often remembers being told to smile more—sonríe más.

“I remember when my father passed away and I used to work at a store as a cashier, at Costless and—that week when I went back to work after we buried him, that’s what I would get constantly, ‘smile smile smile.’ But I think—yes, smiling is beautiful, but at the same time, not smiling is beautiful too,” Cerbantes says.

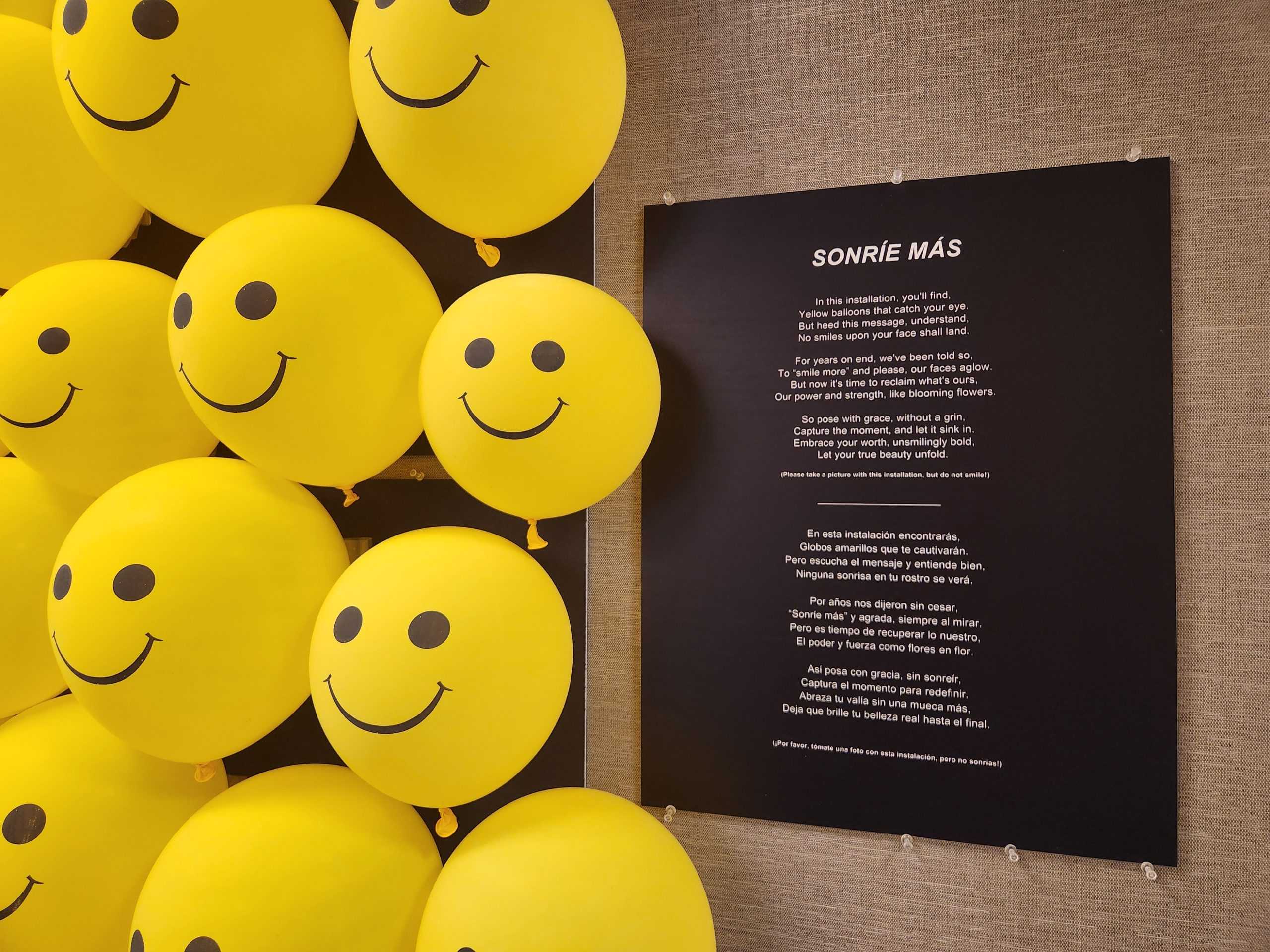

On the far side of the room from the entrance, opposite the TV, is an installation that takes up the whole wall: an arrangement of highlighter-yellow balloons with closed-lip smiley faces.

Beside the balloons is a plaque with a poem titled Sonríe Más, written in both Spanish and English.

“…[I]t challenges the societal expectation for women to constantly smile,” says Oceguerda regarding Sonríe Más. “It encourages women to be authentic and not conform to societal expectations of constant happiness.”

Indeed, beneath both translations of the poem are instructions for the viewer:

(Please take a picture with this installation, but do not smile!)

(¡Por favor, tómate una foto con esta instalación, pero no sonrías!)

Ashna Sing, a former English instructor at Stan State, also felt a connection with the exhibit.

“Coming from a background that is South Asian, American, Pacific Islander, […] I really resonated a lot with the perceptions that have been placed among brown women,” says Sing. “Especially being subservient, having to smile all the time, make sure you accommodate to people’s needs, and I struggled with that a lot.”

Sing said that there are many boundaries and rules being broken in Ocegueda’s art. She sees the exhibit as a place of safety and empowerment that celebrates the culture, all while breaking its hurtful stereotypes.

Event Coordinator, Carolina Alfaro, expressed similar sentiments to Sing.

“[The exhibition] highlights various local folks and telling their dichos and being able to share their stories but at the same time, they’re healing a lot of generational traumas that come with it,” she says.

Alfaro also gives personal insight on coordinating events for the Warrior Cross Cultural Center, particularly when it comes to working with Stan State alumni.

“That’s our favorite part—to really connect to alumni who have a story who have a Creative art background that can really be inspirational to other students. And so, part of the joy that we have in meeting and connecting with the alums and folks that are involved is to really learn more about them, learn about their story, learn about how we can really highlight the work and create some sort of impact,” Alfaro says.

Ocegueda’s story began in Turlock, California, with her ancestry rooted in Atotonilco El Alto, Jalisco, Mexico. Her Mexican-American culture and identity is a major source of inspiration for Ocegueda.

During her time at Stan State, Ocegueda double majored in Studio Art and Communications with a concentration in Media and Public Relations. Since graduating in 2017, Ocegueda has continued to pursue her art and also holds workshops at Carnegie Arts Center.

Her goal for Dichos is to not only to challenge the way that Latinas are perceived and portrayed in the media, but change it as well. She also intends for her work to champion Latina empowerment, further visibility, and promote authenticity of her community.

“The one takeaway from the exhibit,” Ocegueda says, “is to normalize women’s emotions and stop putting pressure on them. It is important to let women be themselves and heal from traumas without being objectified. Supporting other women in their experiences is crucial, as we all share similar struggles. By coming together and supporting each other, we can create a strong community of healing and empowerment.”

To view more of Monica Crystal Ocegueda’s work, visit her website here.