Black History Month has passed by quietly this year at CSU Stanislaus, with the email the Office of the President at the beginning of the month inviting the campus community to participate in the “many activities, lectures and events our campus will host throughout February.”

The email hyperlinked out to the WCCC event calendar, which has only three listings relevant to Black History Month: the month-long Black History Month exhibit in the library, a Black History Month Fair that was to take place on the 11th, and a Black Power Matters lecture scheduled for tonight from 6 to 8 p.m.

However, the Quad was quiet and still during the listed date and time for the Black History Month Fair. This leaves only two major events listed for the whole month.

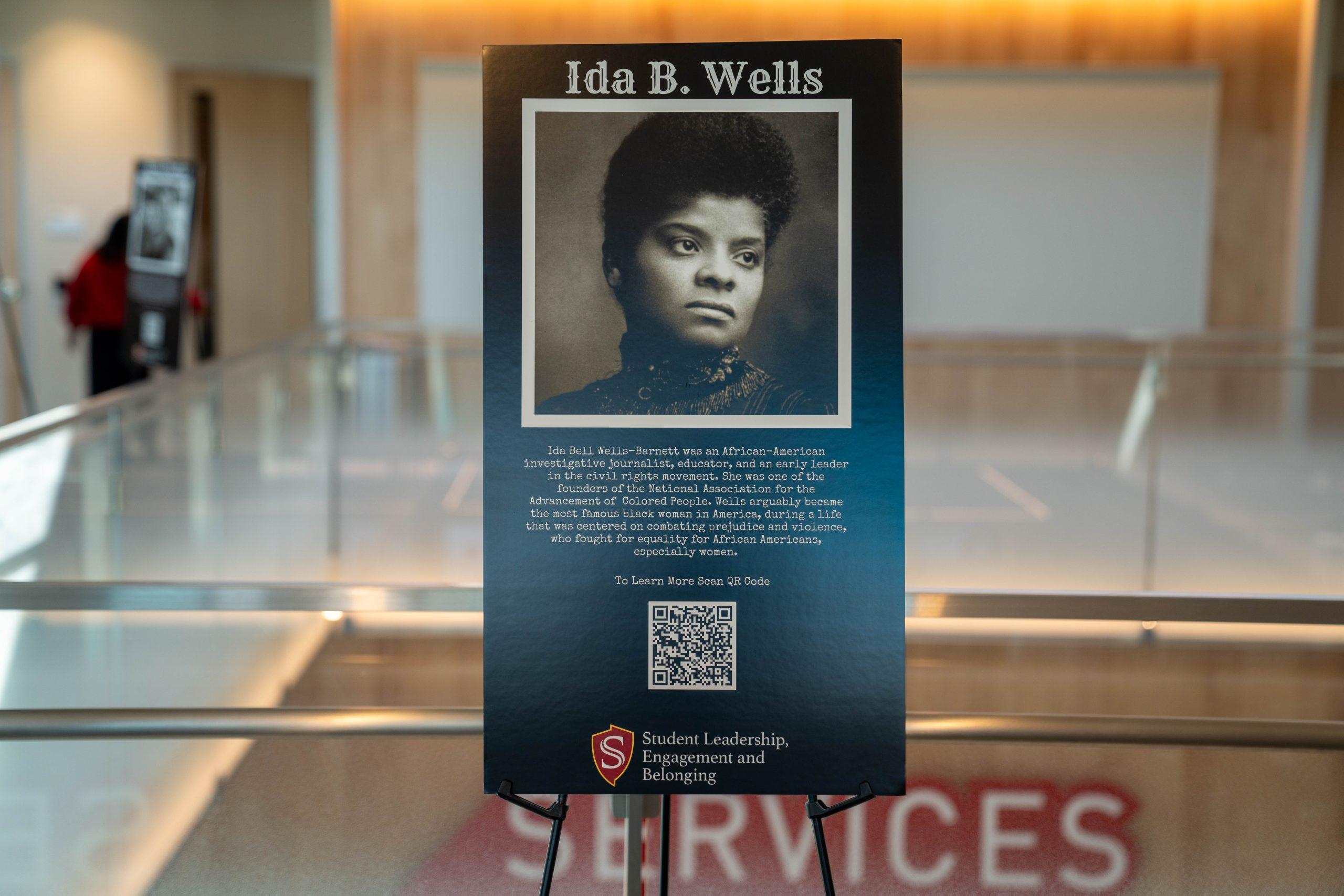

The exhibition on the second floor of the library, meanwhile, invites people to read short biographies of important black historical figures on a series of displayed posters.

These types of displays are par for the course for Black History Month celebrations, choosing to celebrate widely recognized black historical figures and encouraging quiet contemplation of their achievements.

There is a push, however, for Black History Month to be more local, more visible, and more active.

Dr. Ashley Sarpong, an English professor of British Literature, described Stan State’s celebration of Black History Month as standard, being very similar to two out of the three previous universities she’s attended in her academic career.

These celebrations are equally focused on these classic canonical black figures.

“Why is it always these canonical black historical figures?” Dr. Sarpong asked, “Why can’t they find historical black figures in the Central Valley, or even in California, and make that prominent?”

Sarpong only felt that Black History Month was properly celebrated during her undergrad at Duke University. It was there where she was an editor of the Black Student Alliance’s journal, and where student-driven initiatives led to active and jovial celebrations of black history local to North Carolina and sought out to tell the stories of obscure, but vital, black figures.

As part of her time with the Black Student Alliance, she interviewed Nigerian playwright and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, who despite his prize-winning work, flies under most people’s radars.

“It was just really cool to have someone also who wrote, like, in the ‘70s, early ‘80s, still, like, around as a literary figure,” Dr. Sarpong said, “To me that was like, ‘Wow, literature is alive. There are people who make you want to, like, read outside of the canon, and you can still talk to them.’”

Stan State does have its own student organization, the Black Student Union (BSU), whose faculty advisor is Marvin Williams, the Director of the Disability Resources Services.

StanStateBSU was the most recent Instagram handle for the Black Student Union. Their last post was made in the summer of 2022.

Williams confirmed that their account got hacked, and for a while, they weren’t able to reach students. After failed attempts to retrieve the original account, the BSU created another Instagram account.

The union can be reached at BSUStanState.

Marvin says that the BSU’s mission is to help black students embrace their identity.

“What black power looks at is telling people, telling black people that it’s okay to be who you are. Everyone can embrace that, there’s nothing wrong with it. There’s no reason to minimize it, there’s no reason to run away from it,” Williams said.

Williams also says that a major part of their mission is to fight against the erasure of their heritage, and to help people reclaim and rediscover what it means to be black in America and to continue in their fight for rights.

“Preserve your heritage, preserve your culture,” Williams said, “Why? Because it might be all that you have–and it’s a hell of a thing when it’s stripped from you. It’s a thing when your language, faith and humanity is stripped from you and people just expect you to–well–you could get it back.”

Williams says that part of this struggle for equal rights is fighting to have people recognize how the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow still influence how they’re treated today, being brutalized and dehumanized by their own country.

“What’s important is understanding that none of this is about excluding anyone,” Williams said, “The statement ‘Black Lives Matter’ isn’t only black lives matter–there’s an unspoken two that’s there. We get treated like our lives don’t matter, we get treated like our existence doesn’t matter, we get treated like we’re not human–as was the case in this country for a very very long time.”