Aaron S. Coleman is an assistant professor at the University of Arizona who took part in the most recent Artist Talk at Stan State.

Coleman predominately teaches printmaking as well as contemporary, drawing, collage and more.

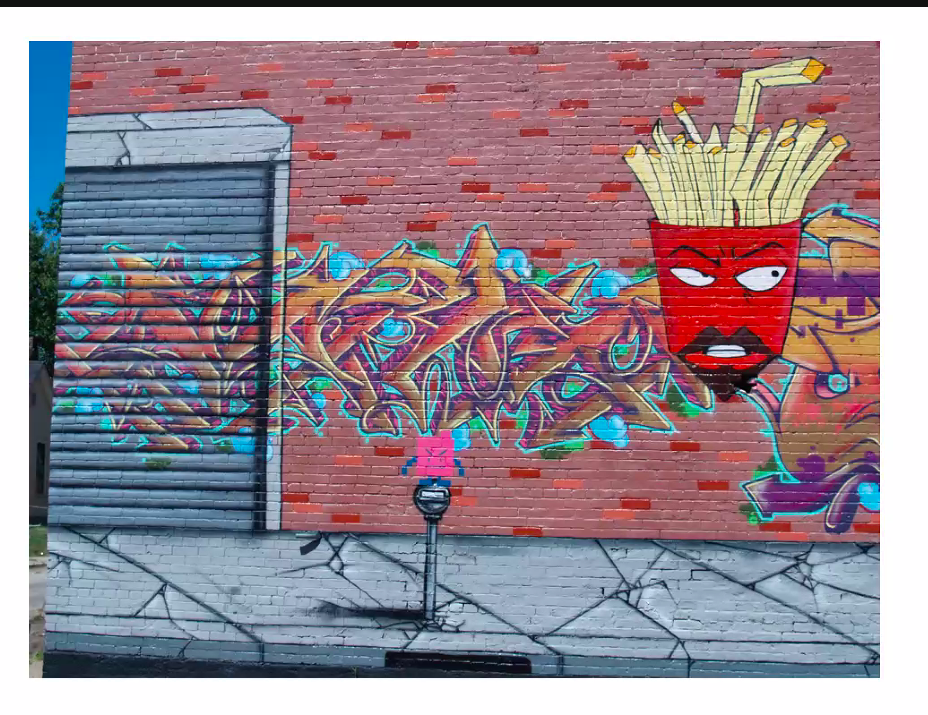

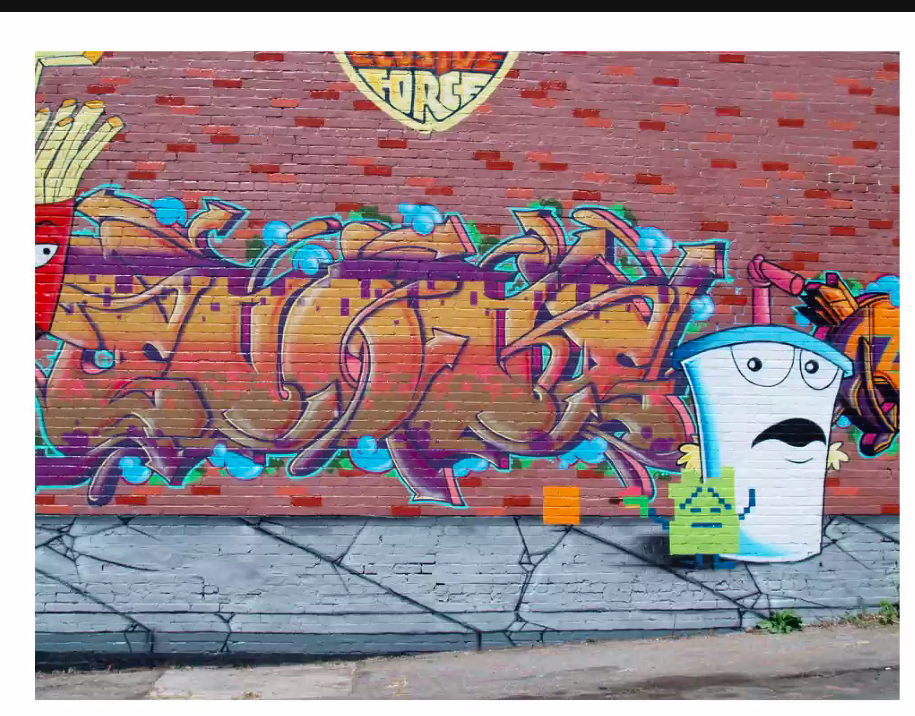

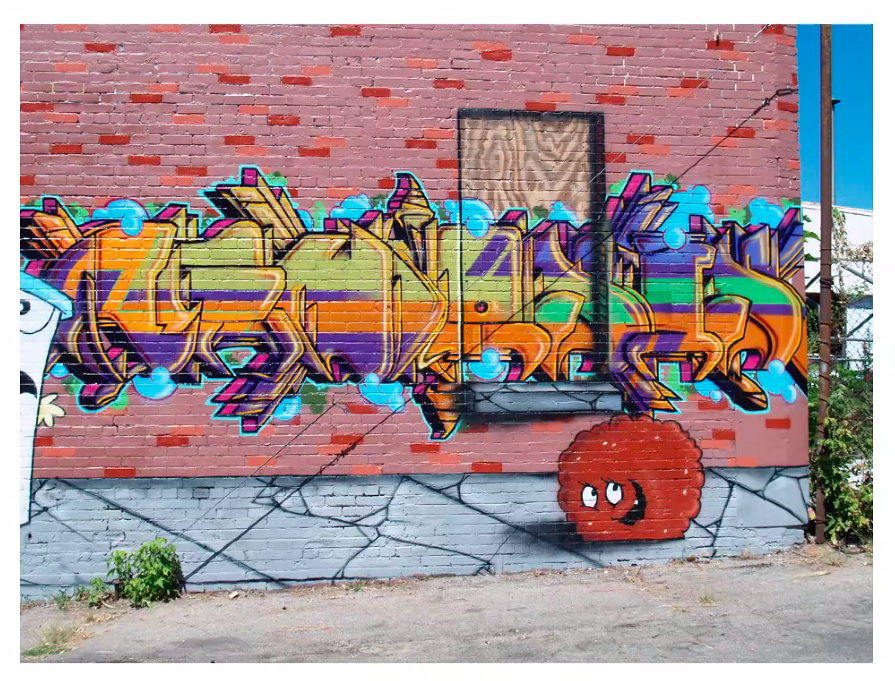

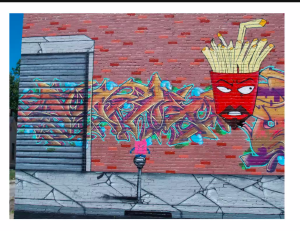

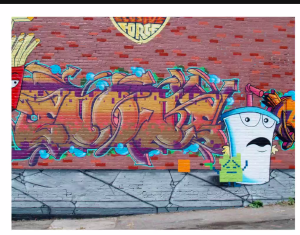

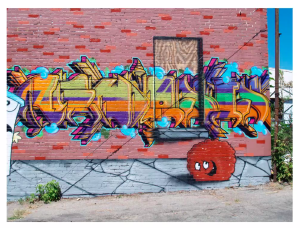

After attending Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis for his bachelor’s and Northern Illinois University for his master’s, Coleman started working on graffiti art.

“I was engaged in graffiti art, and I began to appropriate other imagery as kind of a hangover [in] my interest in appropriating sounds or images in making music or painting walls,” explained Coleman.

For Coleman, hearing hip hop music, especially from Afrika Bambaataa, was engaging because “he was also pulling from different cultures and different eras in fashion different geographic locations to create his outward appearance.”

Coleman added, “My early years were really influenced by hip hop music and graffiti art and this idea that no matter what I was doing I could pull some things that already existed to create new meaning in tell[ing] them in a way that I thought they hadn’t been told yet.”

Coleman also gained experience by painting bridges, trains and billboards.

“I painted a lot of these kinds of large-scale murals, so this particular mineral that the kids in the neighborhood often come out when we were painting and asked us to paint a portrait,” Coleman said.

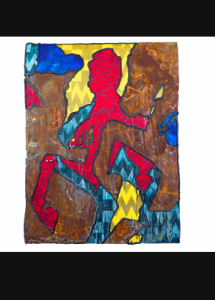

The first series Coleman presented at the Artist Talk was “Pink and Purple.” This series contains 14 small mixed media paintings that demonstrate Coleman’s exploration of altered coloring books from the 1950s.

“These coloring books are used as educational tools to teach children about the colors of the world around them,” Coleman explained. “While there are very few people of color in the book, the pages have yellowed over time and resemble my biracial skin tone. The key on the back of the book gives instructions as to how the pages should be colored, yet missing from this key is any reference to skin tone.”

Coleman explained that he created the pages by following the instructions, while also harnessing various life experiences and stereotypes to make assumptions about the figures in the book.

“When I was young, I heard two people talking and one guy said, ‘He was so black he was purple,’ and as a child I was like, ‘Wow, that sounds really cool’… that image always kind of stuck with me. Purple skin sounded interesting to me and fun and neat,” said Coleman.

Yet, as Coleman got older, he began to understand that they were making fun of the black man.

Coleman mentioned that “Pink and Purple” was all based on a stereotype, on how people can be made fun of based on how dark their skin is.

“This kind of silly notion that someone could be so pale that you can see the blood beneath their skin and so they look pink,” he added.

Coleman explained, “I started to think about the idea of these coloring books as kind of like tools for learning for children…they learn about color in the world [which] teaches them kind of what to expect or what is normal and for better or for worse.”

“Before alteration, the pages are so fragile that they crumble in my hands. Now, more paint than paper, the pages are literally held together by my visual interpretations of history, tradition, trauma and tragedy,” Coleman explained.

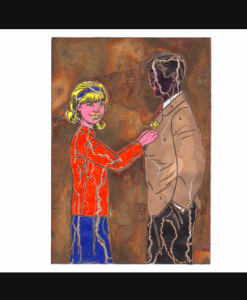

In describing the piece above, Coleman stated, “We have a little girl who is feeding her fish, and that fish takes on that purple skin tone and the red lips and this kind of warped idea that people of color are this thing to be kind of like collected… or marvel.”

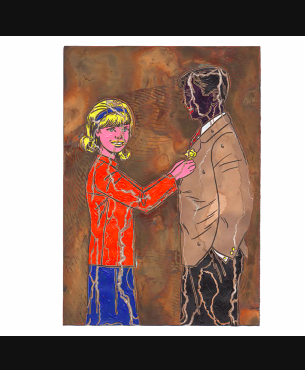

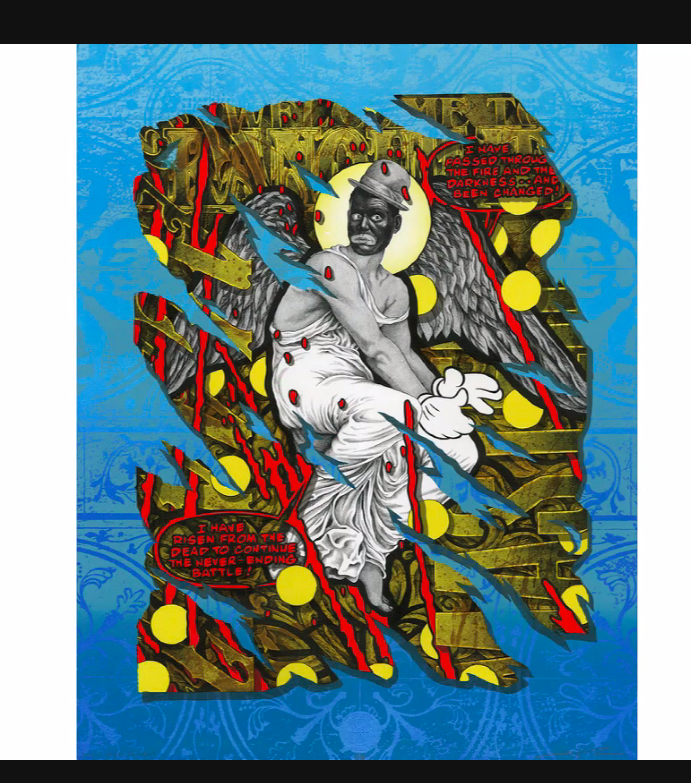

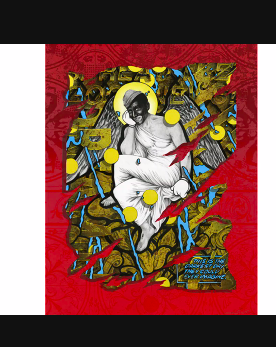

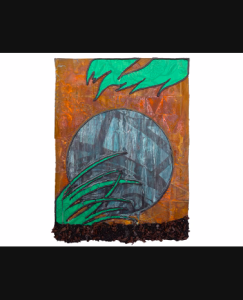

Other paintings Coleman presented during the Artist Talk include the above, titled “Jolly Good Company” and “Dream Lover.”

Coleman described how the events surrounding former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s choice to kneel during the national anthem in 2016 influenced these pieces.

“I just realized that I needed to be talking about issues that impacted me,” Coleman stated. “So I made these two pieces and they deal with the kind of history of blackface minstrel.”

“I have been making work about social political issues [that] impacted communities that I wasn’t a part of,” Coleman stated. Some of these issues included women’s rights, immigration, and issues that impact the LGBTQIA+ community.

“They’re all issues that I care about deeply but they’re also issues that are kind of exterior to my existence,” explained Coleman.

In “Jolly Good Company” and “Dream Lover,” Coleman described how he was “infatuated with this disease gloves, these ideas of these white gloves as kind of a symbol of white purity and also thinking about putting a white glove on to run your finger across the surface of something to see if it’s dirty.”

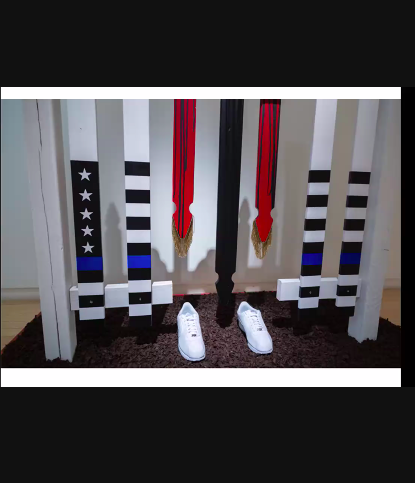

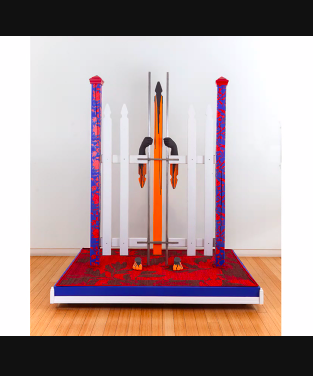

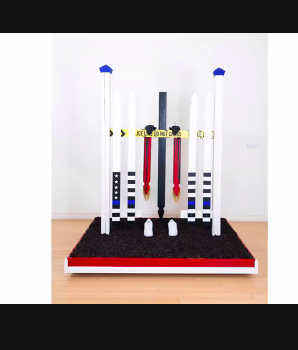

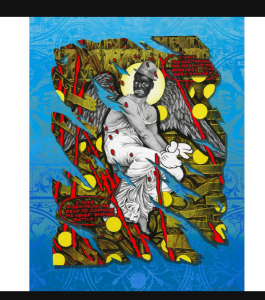

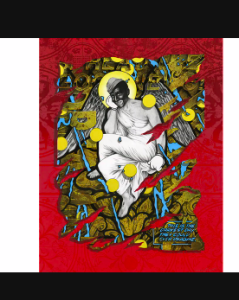

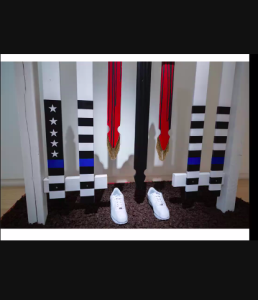

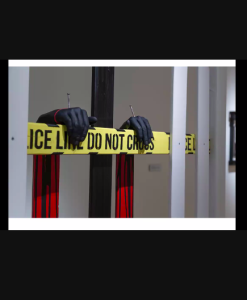

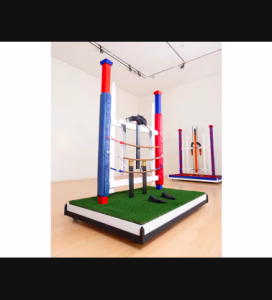

Another exhibition Coleman presents is “True and Livin’.”

Each of his three sculptures in this exhibition are built around the structure of a picket fence, and each embodies or traps a black figure.

Coleman explained how the picket fence in his exhibition “becomes a structure or a mechanism for which white supremacy can operate.”

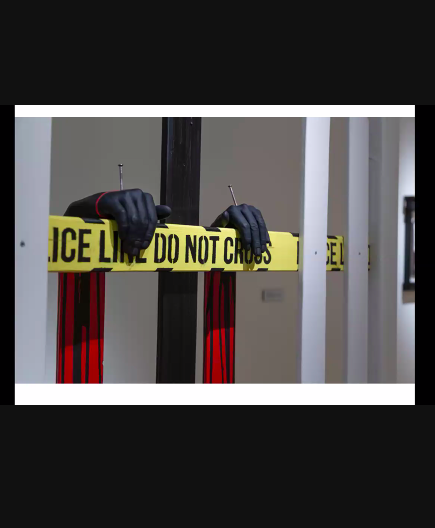

The sculpture not only aims to address police brutality, but it also talks about what it means to be on the other side of the crime scene tape.

Coleman explains how these sculptures “bring integrating ideas of religion and the complicity of the church in perpetuating or benefiting from racist ideas, particularly in the era of Jim Crow.”

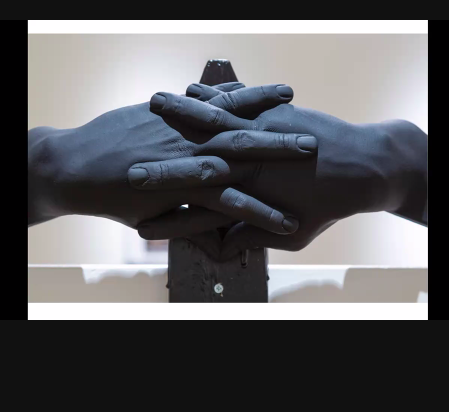

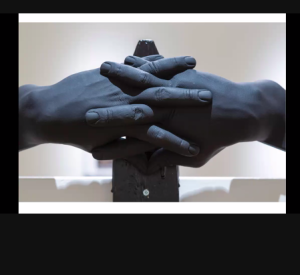

“The hands perched on the police tape transition down into what would be the stoles of a priest,” Coleman described. “The central figure creating that cross. There’s a detailed shot of the hands nailed to the cross to resemble the crucifixion.”

The foundations of these pieces are composed of recycled playground rubber mulch and Astroturf rubber crumb. Resting on the ground in several of these sculptures are pairs of Nike Cortezs, or Nike Dopemans, a shoe Coleman described as “a symbol of blackness.”

“The [shoes] are resting in a bed of recycled playground mulch, which is an indicator that these kinds of issues can happen anywhere, they don’t just happen to adults. They happen to kids; they happened on playgrounds; they happen on schools or in schools. They can happen anywhere,” he continued.

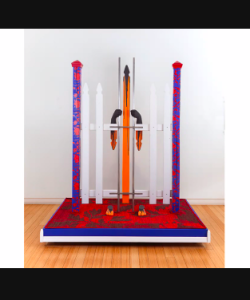

The piece above is titled “Home Away from Home.” Coleman explained that this sculpture deals with the criminal justice system, which he said feels a little strange to him due to the fact that it includes the word “justice” in its name.

“We can call it the prison industrial complex or mass incarceration, which disproportionately impacts black and brown… the figure cut off at the legs,” said Coleman.

The figures in these sculptures were casted with Coleman’s hands and feet.

“I was really trying to make the surface physical, and when the sculptures started, I didn’t want to make objects, I wanted to make people. I wanted to make big sculptures that were my size so that when you encounter them, you’re physically confronted with a figure that is my size. I’m 6-foot 5 and 250 pounds. I’m very aware that the way I look and my size and stature could be the death of me,” Coleman stated.

Coleman also explained how the shootings of black folks at the hands of police officers inspired this need for “physicality” in his work. “We just [weren’t] getting it out of my system and so I needed this kind of like physicality, and I think that started to come through in the paintings,” Coleman said.

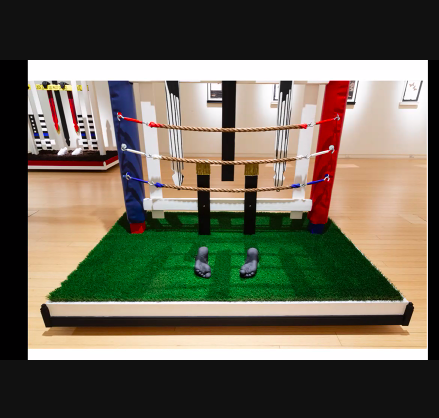

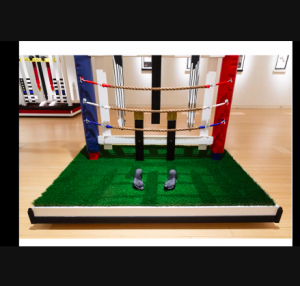

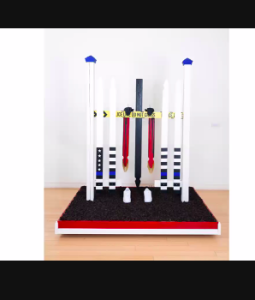

The above piece is titled “Rope or Dope.” Coleman’s initial inspiration for this piece was the story of his father growing up with Cassius Clay, also known as Muhammad Ali.

Coleman believes that this piece is extremely relevant to what is happening in society, as Ali was an important figure for the Civil Rights Movement.

The picket fence once again works as a kind of main structure or a stand-in for the way society functions as it surrounds a black figure. This figure is kneeling on both knees in the grass. According to Coleman, something to notice in all of the sculptures in the “True and Livin’” exhibition is that the figures are cut off at the legs in an effort to symbolize the kind of immobility that people of color have suffered in this country.

In “Rope or Dope,” the figure has its “hands and fingers interlaced behind its head as it assumes the position of someone being detained by police…you also have the kind of formation of a boxing ring in the figure is pinned between the ropes and the picket fence, and of course the title takes its name from Muhammad Ali’s famous strategy of the rope-a-dope where he leans against the ropes and lets his opponent tire himself out until he can no longer fight effectively,” added Coleman.

Coleman explained how accurate a metaphor it was for a way that people of color have endured the opponent of white supremacy.

He then mentioned how he purposely changed the title of the piece. “I have changed the title from ‘Rope-A-Dope’ to ‘Rope or Dope,’ hinting at the rope of lynching and dope referring to the War on Drugs.”

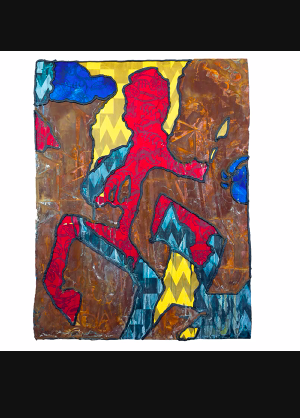

Another series Coleman presented in the talk was “Monumental Shadows.” It consists of nine large-scale mixed media paintings that present stacked silhouettes of confederate statues, materialized through bronze, iron, tar and screen-print on paper.

Coleman discussed the looks of the screen prints.

“The oxidized and corroding metals elude to the man-made construction of both physical objects and problematic ideologies, their precarious foundation, decaying façade and inevitable demise,” he explained. “The floral patterns of Colonial Crewelwork embroidery and African Kente cloth motifs are stand-ins for oppressor and oppressed, villains and heroes. Mimicking stained glass windows, the works in Monumental Shadows are explorations of authoritarian systems of power. In this case, under the microscope is the legacy of the church and its role in perpetuating white supremacy and the radicalization of indigenous spiritualities.”

Here are two different pieces from the series.

Check out more of Coleman’s artwork on Instagram, art page, or virtual exhibit with the catalog of another exhibition, “Things Fall Apart.”