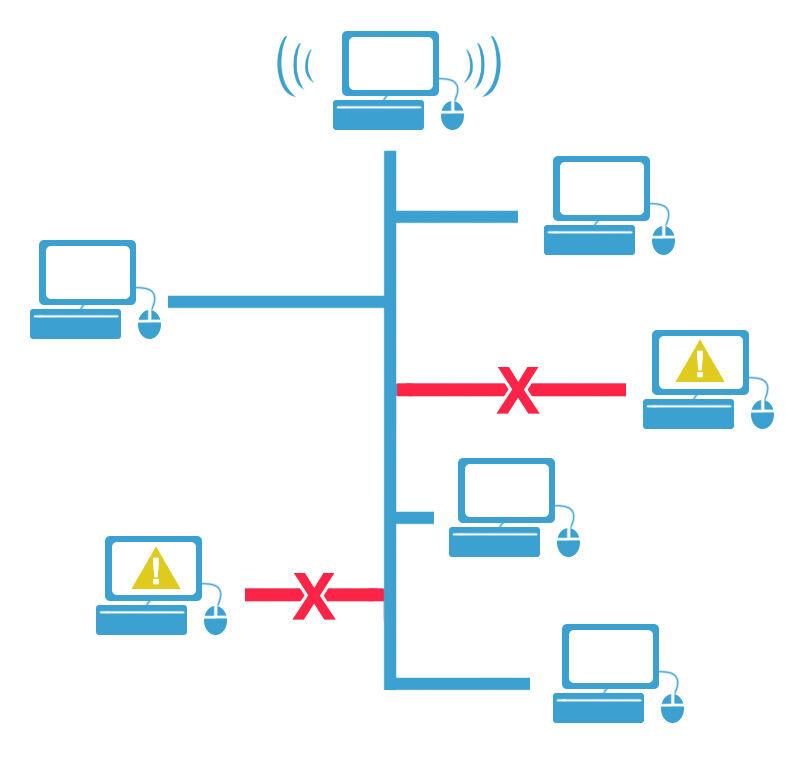

With the online transition, Stan State professors have been placed into learning alongside the student body. Between the mass implementation of Canvas and needing to adjust their lessons and teaching style to Zoom, they have had their own share of difficulties in the new climate.

Learning online comes with its difficulties. Faculty and students agree that not being able to have face-to-face interactions takes away from the quality of the classroom and college experience.

In regards to the loss of personal connection and daily routine that professors experienced on campus, English professor Dr. Scott Davis says, “I miss the smell of the book-binding glue in a library. I miss the interaction in the hallway with people. I miss having a cup of coffee in the classroom. I definitely miss standing up to a class. I hate sitting down and talking over Zoom.”

Davis joked that there’s been some benefits to the transition. “On the other hand I haven’t worn shoes for a lecture since February! So maybe I don’t want to go back.”

That loss of face to face interaction also adds a layer of difficulty in interpreting student involvement. As Cultural Anthropology professor Dr. Ryan Logan explains how through online, he cannot see a student’s involvement if they are not speaking up and it makes it difficult to gauge where students are at in the class. “It’s a lot harder for me to tell as a professor if y’all are really engaged. I can’t survey the classroom, I can’t see the engagement.”

For professors who have always taught class in person, they have needed to adjust quickly, often switching their curriculum in order to operate in the new setting. For Logan, one of his main goals with the online transition was “to make it feasible and fun, but not go overboard for students and not make it stressful.”

Similarly, English professor Dr. Jesse Wolfe mentioned that he “tried to construct syllabi that would be Zoom friendly,” stating that as his reasoning for making his classes this semester all poetry. Both professors wanted their class to be as online friendly as possible when teaching synchronously over Zoom.

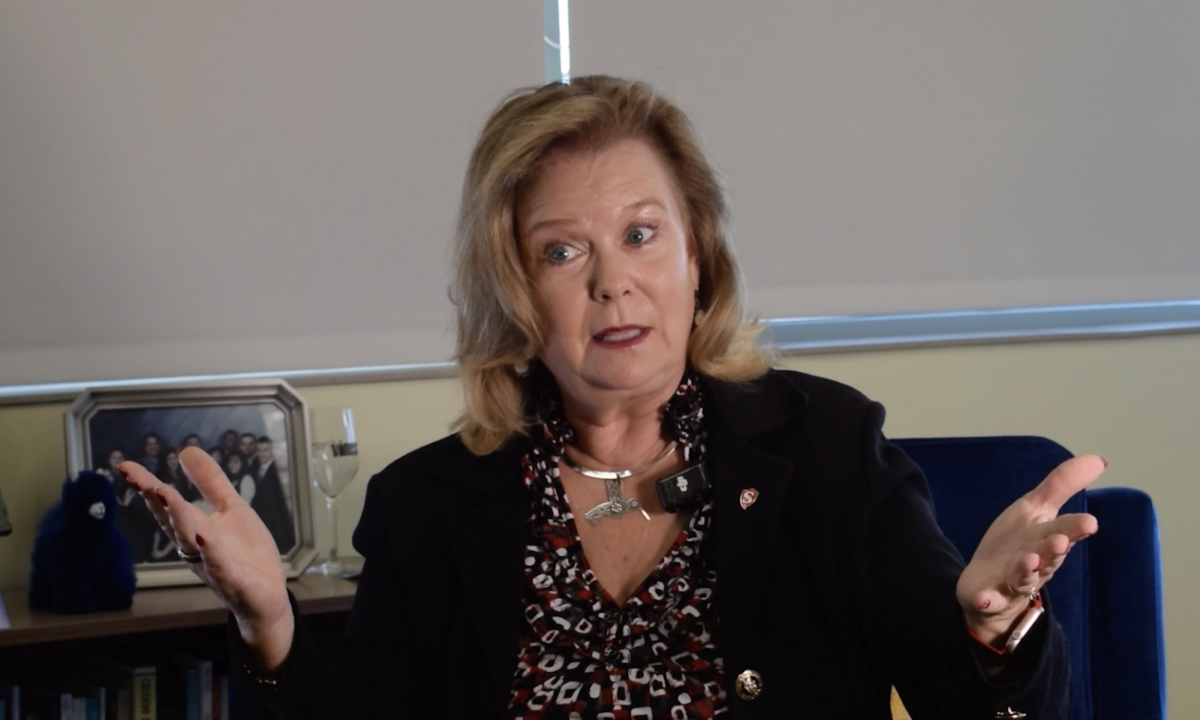

With Zoom, students have the liberty of choosing if they want to be seen in class that day. With a click of a button, students could easily turn their cameras off and remain unbothered during lecture. This can be detrimental in many ways because it takes away from the connections that one would have at a physical class on campus. In regards to this unspoken camera rule, English Lecturer Pam Young says, “I do require the camera to be on except for the students whose voices turn robotic if the video is on. I feel so lost trying to teach to a screen full of blank profile pictures.” She adds, “I told my classes that their faces give me what I need to be able to show up for them, and I thank them for showing up. It makes it much nicer to teach now.”

Other professors, such as Logan, view keeping the camera on as a means to “foster that classroom atmosphere,” While they would prefer for it be on, they do understand that it is not always an option.

They also see it as a way to keep track. Wolfe acknowledges that he wants his students to participate and if they don’t have their camera on, he cannot really tell if they are present, contributing to his practice of cold calling as an indicator.

There are elements of class that are not easily replicated over Zoom. In a classroom, students are more engaged and are eager to share answers amongst the class. Over Zoom, there is an odd dynamic in regards to speaking or asking questions during class. English Professor Dr. Kate Hope says, “I miss the messiness of teaching in person. I never know how it’s going to go, but I like that. I miss the unexpectedness of a student asking a question and me being able to elaborate on it. This doesn’t happen as much with online learning.”

Professors with more interactive courses that involve activities are not as able to fully embrace that style through a Zoom format. Something like group work is more difficult when you have to put people in breakout rooms and it separates students entirely, leaving little room for monitoring or questions.

Logan explains how for him, “when I jump into those groups, it takes a while. I have to jump into the room, leave the room, jump into the classroom, and then I have to jump into the next room. By the time I get to the last group they’re either done, or the first group has been done and they’re just sitting there. It starts to feel like a waste of time, and I don’t want to waste time.”

Despite these struggles, Logan has mentioned an ability to adapt and find several new types of interactive activities to replace what no longer works in the new format that he can use even past online.

Professors have also found some distinct benefits to the Canvas transition. Though there was a learning curve, Wolfe has mentioned that “I found Canvas and Zoom to be quite user friendly,” indicating that it has worked well with his teaching style. Like Wolfe, Logan also agrees that Canvas has been easier to work with than Blackboard was.

In conjunction with the transition from in person to online learning, professors and students both have to adjust to the transition from Blackboard to Canvas. “I love Canvas heads and tails over Blackboard,” Hope says. “I think it is more accessible and intuitive for me. From a student’s lens, I hope it is the same for them as it is for me. To me, it is more versatile.”

There have been a multitude of adjustments needed on all sides that have also led to beneficial discoveries. Wolfe points out “there is a good deal of behind the scenes work that goes on… the transition is stressful for everyone,” and students and professors are understanding of these facts. Ultimately, everyone is learning and adjusting, and we all need to remember that.