After three years of being locked in a six by nine-feet cell, 23 hours a day, in a California State Prison, the time had neared. I knew my release date was coming. I was scared. I was anxious and didn’t know what I was going to do. Three years of incarceration with no rehabilitation didn’t really set me up for success.

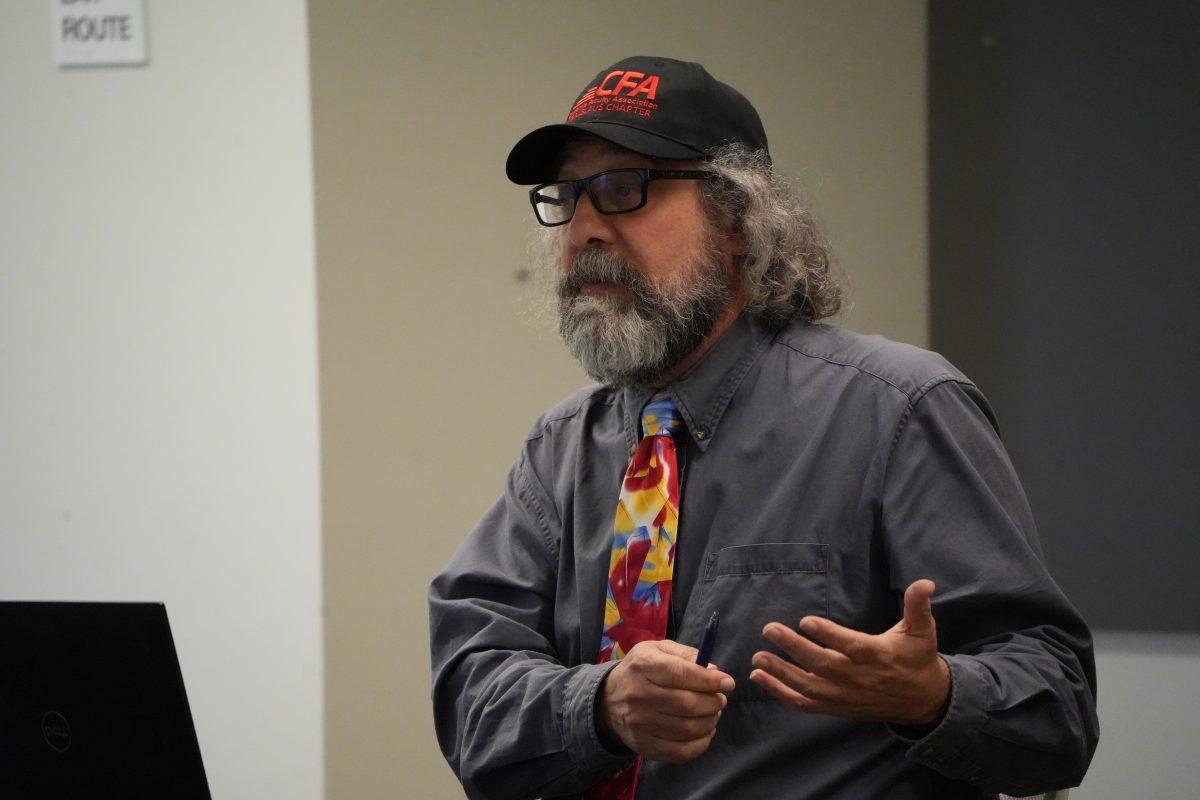

I wasn’t alone. According to the website prison policy, there are 2.3 million people incarcerated in America. According to Dr. Blake Wilson from the Criminal Justice Department, a majority of those in the criminal justice industry see punishment and education as incompatible. “If someone comes out of prison with a college degree and skills, it is hard for us to align that with the idea that you have been punished,” Wilson said.

I knew that my chances to stay out were slim to none. I didn’t have any skills or an education that would allow me to compete in the job field. Most likely, I was going to do what most of the people that get released from prison do, get out with no skills and continue participating in the activities that got them incarcerated and eventually recidivate. It is a revolving door.

I saw it while I was in Pelican Bay State Prison. During the two years I was there, I saw people get released and come right back on a violation or for a new charge. That is the never-ending story in America’s prison system.

The recidivism rates in America are staggering. “If you go to the penitentiary in California, there is a 60 percent chance you are going to get out and go back to prison,” Wilson said. According to the Bureau of Justice website, 83 percent of those released from prison will return within 9 years of their release date.

Finally, I had enough. I was sitting on my bunk in San Francisco’s County Jail, four days before the Fourth of July. I was told that I might get released on my own recognizance, but I was on probation, so I didn’t believe that was possible. Then, while I was sitting on my bunk, I prayed to God. I asked him, please get me out of jail so I could spend the holiday with my son. I promised I would give up the negative lifestyle that I adopted as a teen and go to college.

Education has statistically proven to reduce the rate of recidivism. For those previously incarcerated inmates that get a bachelor’s degree, the recidivism rate drops dramatically. According to the website , those with bachelor’s degrees have a six percent chance to recidivate compared to 60 percent of those without degrees. Wouldn’t it make sense to give those that are incarcerated a chance to educate themselves?

According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) website, thanks to the Sept. 2014 passage of Senate Bill (SB) 1391, the California Department of Corrections and the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office have signed an agreement to expand and increase inmate access to community college courses that will lead to degrees, certificates or will transfer to a four-year university.

For most college students, navigating through the CSU system is a difficult process. So, for someone who has been incarcerated and who is new to the college life, it can be nerve racking. When I made the decision to enroll at Modesto Junior College (MJC), I was nervous and did not know where to begin. I was lost and discouraged to the point that I almost decided to not pursue an education. Thankfully for those who are dedicated to beginning a new chapter in their life, there are programs dedicated to helping those individuals. Project Rebound is one of those programs.

Project Rebound was started by John Irwin in 1967, to matriculate people into San Francisco State University (SFSU) directly from the criminal justice system.

“Rebound is definitely a support network in higher education for formerly incarcerated people, ran by formerly incarcerated people that know a little bit about that transition,” said Jason Bell, Regional Director of Project Rebound at SFSU. Rebound receives letters from inmates in California’s prisons, asking for information about receiving an education.

“We have an office coordinator that handles 60-100 pieces of mail a month from people all over the state inquiring about what it takes. It takes people that have a connection to the university to know how to transfer, what classes you need for your core, general education, and a major. We are that connection,” Bell said. The program that started at SFSU has spread its success into eight other CSUs.

Being the first in my family to go to a university, as well as being previously incarcerated, I know that it would have greatly helped me if this program was on campus. To be able to talk to and have a support system of people that have gone through the rough transition from prison to higher education would have made it easier for me. Being able to relate to someone and to open up about specific issues related to our success could be beneficial for success.

According to Stan State’s Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Kimberly Greer, while we are the only CSU in the Central Valley that doesn’t have a collaboration with Rebound, “we are initiating the steps to get the program here. We are trying to network with MJC, our local community college, so we can start up a partnership and then we can funnel previously incarcerated people to transfer from there to here,” Greer said.

“We have to take the proper steps and go through the proper channels to get the program here on campus. I have spoken with President Junn about the program and she is all for it being on campus,” Greer added.

Being a felon, I was always under the assumption that I was unable to vote because of mistakes that I made in my past. In California, that’s not true. I was informed that if I was not on parole, I could vote. That gave me hope that my past might not be able to haunt me forever. This midterm election was my first time participating in my civic duties.

Being a felon has disenfranchised millions of Americans across the world from voting. A study conducted in 2010 concluded that 19 million individuals in America have felonies on their records. According to the 6.1 million Americans are unable to vote because of felony convictions. Recently, 1.4 million felons have regained their right to vote in Florida. On Nov. 6, 2018, Florida passed proposition 4 with 67 percent of voter’s voting yes to restore those that have been convicted of a felony with the right to vote.

Now, I can reflect on my past and understand that it isn’t my future. My past doesn’t define who I am. Through my own persistence and dedication, I can say I did it. I am no longer a statistic or known as inmate number F82070. Now, I am a Stan State student with a 3.93 GPA, with hopes to motivate those that don’t think they can do it, into doing it.