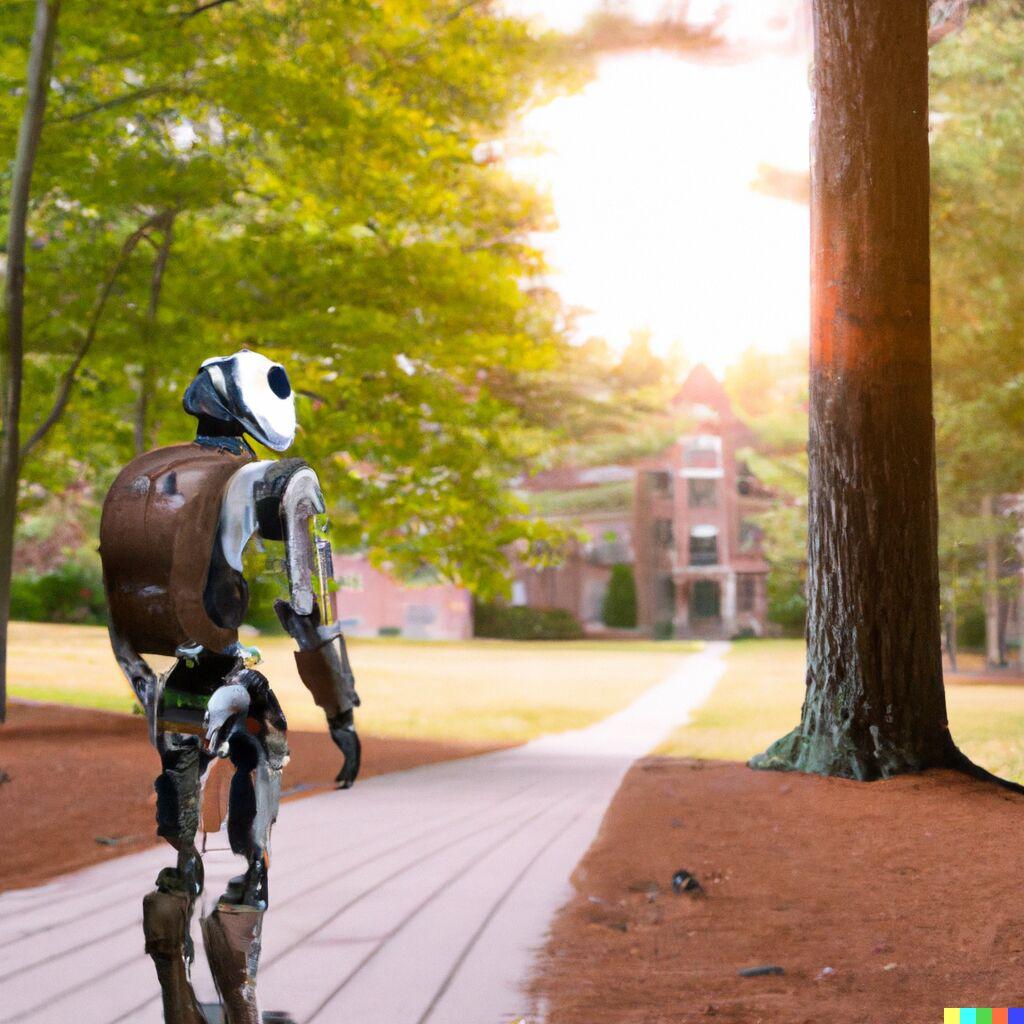

College is a time when students are exploring their identity and finding their voice. Whether it’s a painting, a sculpture, or even just a doodle, art is a way for people to express personal meaning into a work of their own volition.

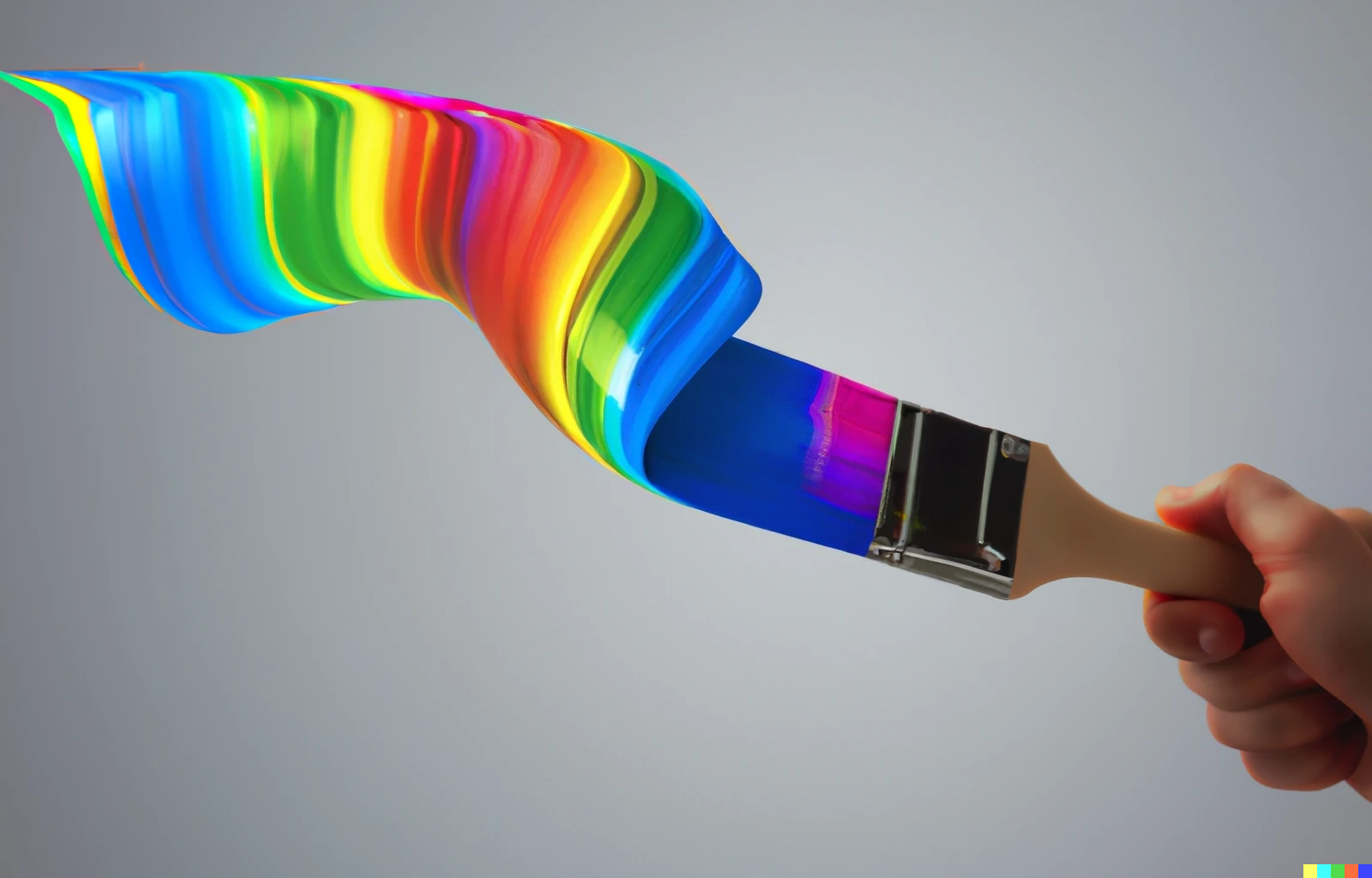

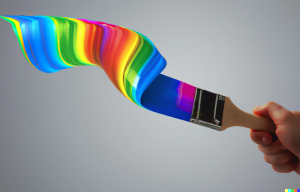

With the advent of technology however, there are now even more ways to express oneself. In just a few short months, DALL·E has taken the art community by storm. The online web platform has enabled users to produce some of the most impressive and realistic artificial images ever seen. And now, it’s available to anyone with an internet connection.

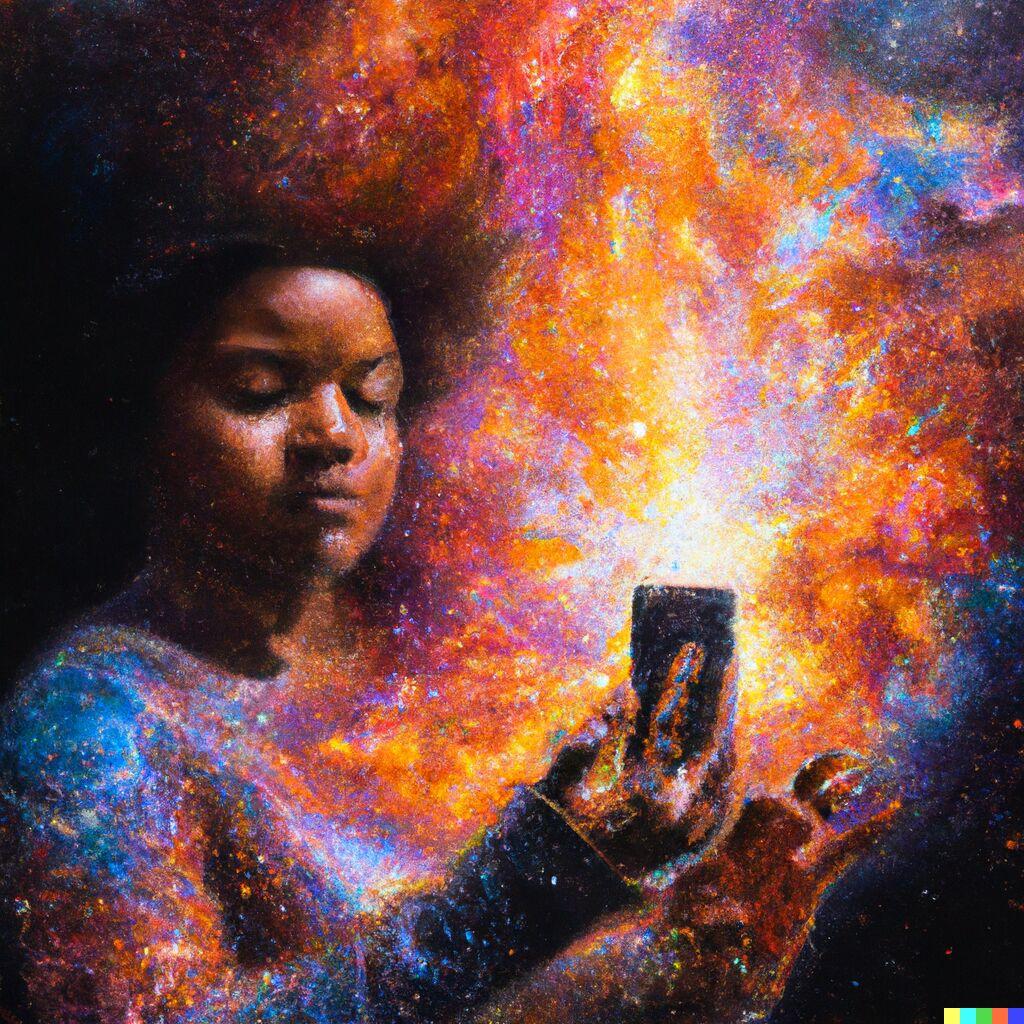

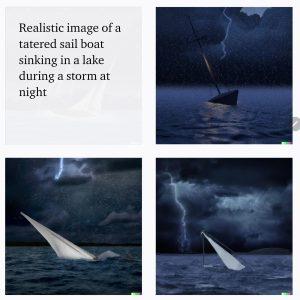

DALL·E 2 is a machine learning model created by OpenAI that allows users to create images simply by describing an idea in a prompt. The platform then uses artificial intelligence to generate four unique images based on the given description, from its training on millions of online images and their metadata. Other features of DALL·E include generating variations of a given image, and ‘painting’ in selected areas to add or expand new details.

With such potential, it should come to no surprise college students have taken a great interest into DALL·E and its implications for the world of art. What may be surprising however is the rapid rate at which the tool is being adopted already within CSU Stanislaus’s Department of Art.

Introduced this year, the second iteration of DALL·E was previously only available in a waitlisted beta. On September 28, 2022, OpenAI announced in a blog post its removal of the waitlist, granting access to the model through any registered account.

Students in the Art Department quickly jumped at the opportunity and have begun implementing DALL·E to assist in the art creation process.

BFA student Shelby Woodings expressed their excitement for DALL·E and its capabilities as a whole.

“I actually took one of the artists that I’m inspired by and put this work, uploaded it into DALL·E, and it gave me variations that I thought were very interesting,” Woodings said.

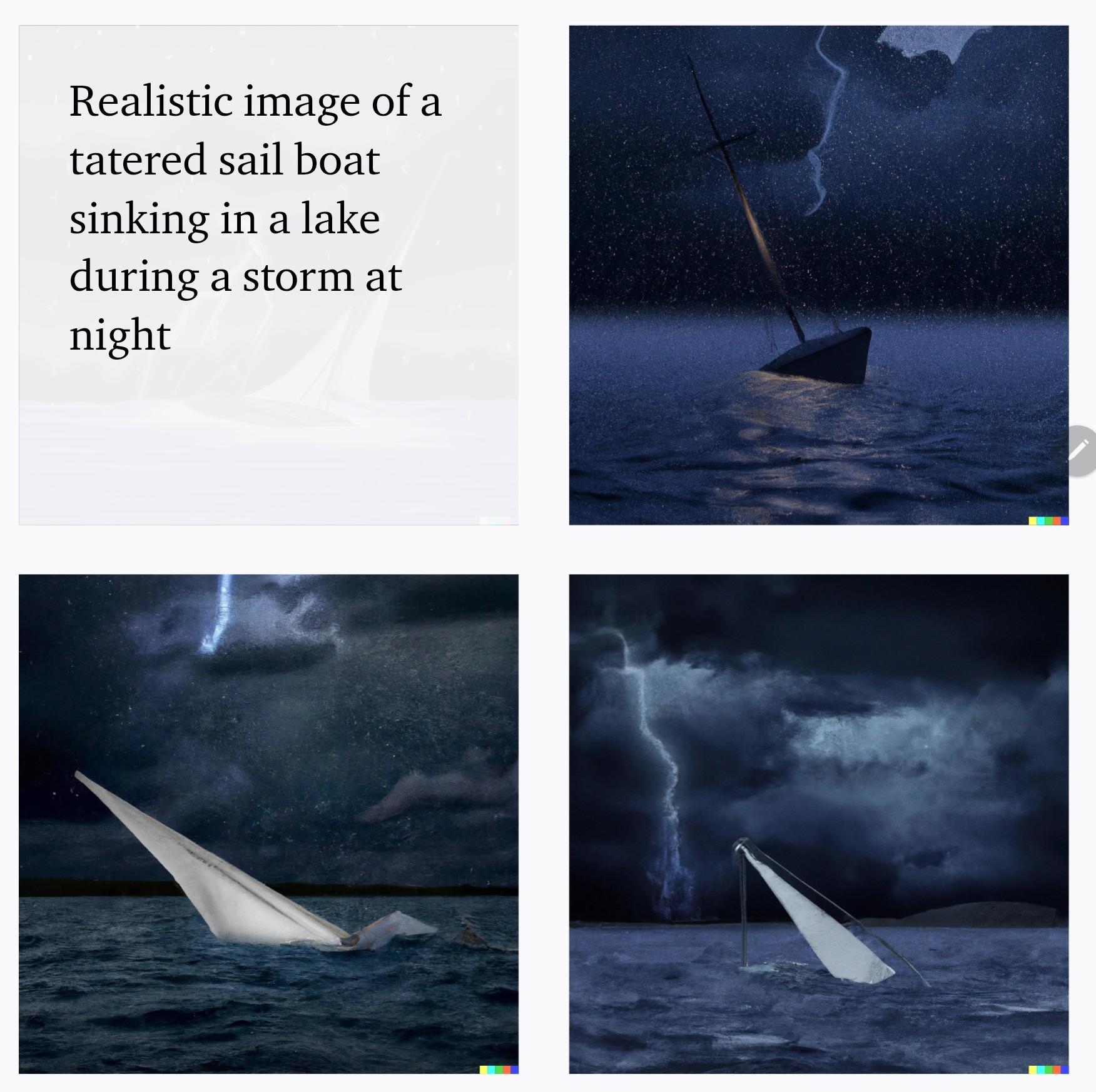

In the same vein, BFA student Kyle Silligman shared his artwork which rested beside him, a large canvas painting at the sculpture lab. For his piece titled “Come Sail Away”, Kyle explained that he was able to use DALL·E to brainstorm and generate his ideas for the painting, and even shared the original images he used as reference for the final painting.

“I use it like a tool within the creative process. Just like with Google or any of your historical research when trying to develop a piece,” Silligman said.

Faculty and staff at the art department are well-aware of students’ use of DALL·E and welcomed the breakthrough innovation.

Instructional Technician Alex Quinones said, ”I think a lot of them are really adamant to use it just because of the time we’re in, and I know a lot of people adapted to COVID through using technology. So they realize, ‘Okay, I can use this tool and it is valid. So why not use it?”

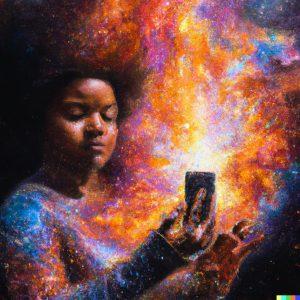

This sentiment regarding DALL·E is not shared among all artists however. The role of AI models in art, as well as the validity of the generated images as “real art” — worthy of equal appreciation and value as human works, has been called into question by the art community.

Dr. Daniel Edwards, associate professor of sculpture, expressed his opinion on the matter.

“I would say it is not as valid as art created by humans. I would say it’s a tool that can be used for it. But that’s just from my perspective of working with my hands. I think what it is doing is creating a new kind of artist,” he said.

Professor Edwards also explained that human art speaks for itself, meanwhile AI art is spoken for by the prompt. This difference could impact the art’s ability to evoke emotion independently.

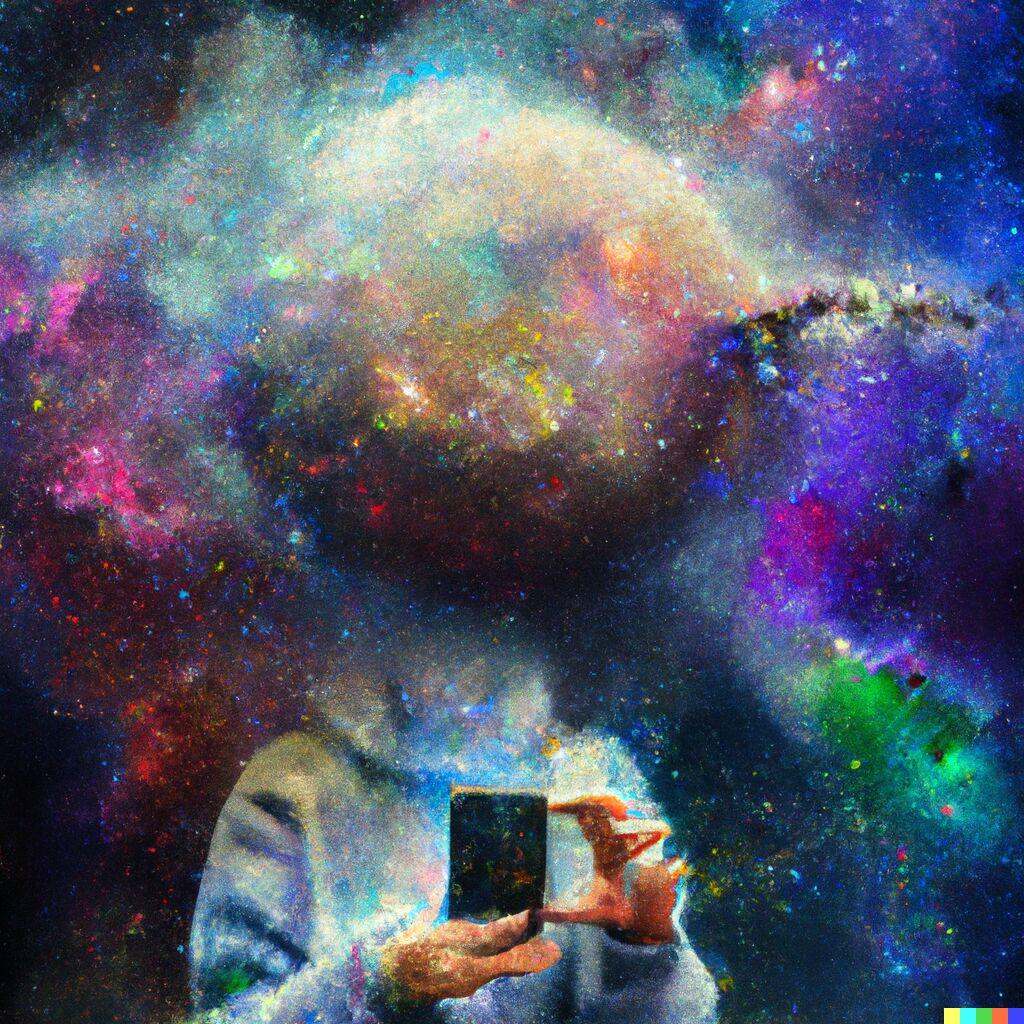

Jessica Gomula-Kruzic, associate professor and co-director of the creative media program, also chimed in on the validity of AI Art in an interview, arguing instead that DALL·E is ultimately intrinsically human at its core.

“There is still definitely human interaction in it,” she said, “People created the software, and then people are deciding what the prompts are, and then people are also deciding which results they like best.”

Gomula-Kruzic elaborated further, stating that now instead of art being a question of who can manipulate the paint the best, with DALL·E it is now becoming who can input meaningful words to create the most interesting image: “You become more of a wordsmith than a painter.”

Tools like DALL·E can help eliminate barriers that hindered disabled or low-income students who lack access to expensive software from expressing themselves.

However, DALL·E introduces its own set of issues

DALL·E is not free, and eventually requires the user to purchase additional generations in a credit system to keep the computationally-expensive service running. DALL·E also has an extensive Content Policy prohibiting the generation of certain images and prompts, which can limit self-expression when false-positives or misinterpretations occur.

Stan State is addressing these barriers in their own way through Warrior Fab Lab. Launching later this semester, this creative space located within the Vasche Library provides free access to various tools to help students in the campus community to express themselves.

So the DALL·E platform is just one example of the amazing things that can be accomplished when a community collaborates together in an effort to be more inclusive.It’s clear that advancements in technology and AI are changing the landscape of art and creativity, and college students at the Art Department are at the forefront of this change. What could be next?